Pelage scoring of released wildcats

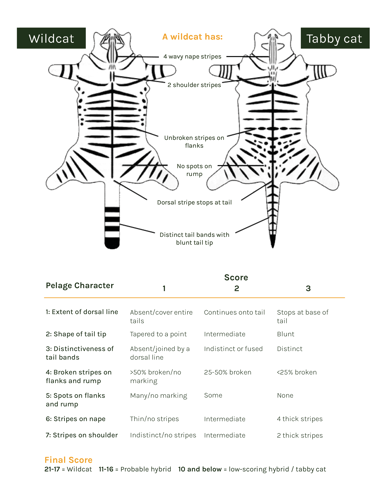

Wildcats in Scotland have historically been identified by their pelage or coat markings. This method was developed by Dr Andrew Kitchener in 2005 and uses seven characteristics to identify if an individual is a wildcat. It was developed by assessing the pelage of historical wildcat samples taken from across Scotland, as well as wildcats in captivity in the UK, in response to the growing understanding that hybridisation (interbreeding) between wildcats (Felis silvestris) and domestic cats (Felis catus) was significant in Scotland. Academics and conservation practitioners needed a way to differentiate between the two species and their resulting fertile off-spring, known as hybrids.

This method gives a score of between 1 (domestic cat trait) and 3 (wildcat trait) for seven key pelage or coat patterns. Using this method, individuals that score 19 or more out of a possible 21 for the resulting pelage score are classified as a wildcat.

Over time, technology progressed to allow the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland (RZSS) to develop a genetic test using a similar process related to human paternity and ancestry testing which can be used where access to genetic samples are available. Now, the level of detail available to help distinguish wildcats from domestic cats and their hybrids is highly dependent on the situation in which the animals are observed and what data is available to make these observations such as the quality of the pelage data and ability to perform genetic tests.

Following the development of this genetic test, in 2016 and 2017, all breeding captive wildcats were genetically assessed for levels of hybridisation. Data published in the peer-reviewed Journal of Evolutionary Applications in 2019 details these genetic results and shows the levels of wildcat DNA found in wildcats in captivity in the UK are considerably higher than those found in wild-living cats in Scotland. Only wildcats that passed the minimum genetic threshold were used for further breeding, and most cats in the breeding programme scored much higher than the minimum threshold.

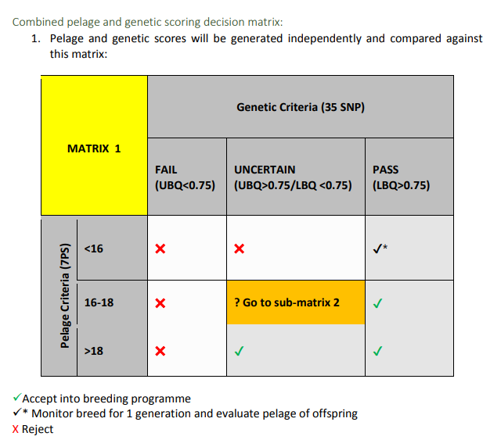

Following the development of this genetic test, wildcats in the UK’s conservation breeding programme were subsequently managed using a combined genetic and pelage scoring matrix, as outlined in a report produced as part of the UK’s Scottish Wildcat Conservation Action Plan, written during Scottish Wildcat Action, the first national conservation plan with a vision to restore viable populations of wildcats north of the Highland fault line. This scoring matrix was also discussed in the peer-reviewed Journal of Evolutionary Applications. The decision was made to use a combined approach of both the genetic scores and pelage scores of individual wildcats as each testing method provides different, yet equally valuable information about wildcat genetic ancestry.

Using this methodology, individual animals can fall into the following categories. These are:

- Accept into breeding programme (individual has a pelage score of 16 or over and a genetic score of over 75% OR individual has a pelage score of over 18 and a genetic score on the cusp of 75%)

- Monitor to breed for one generation and evaluate the pelage of off-spring (individual has a pelage score of under 16 but has a high genetic score)

- Reject (individuals with a combination of low pelage scores and low genetic scores)

Using this method has helped to ensure that as much valuable wildcat genetic variation is preserved as possible from the captive population in Scotland whilst simultaneously minimising the level of domestic cat genes and ancestry in the captive wildcat population.

All of the wildcats born at the conservation breeding for release centre at Highland Wildlife Park, released this summer as part of the Saving Wildcats project’s first trial releases under license from NatureScot, have genetic scores that well exceed the minimum genetic threshold (which is 75% - equivalent to a cat having one grandparent as a domestic cat).

Prior to release, the wildcats had their pelage scores assessed by members of the Saving Wildcats team and by independent expert, Dr Andrew Kitchener. While the majority of the released wildcats have scores of above 16, two of these individuals have just slightly lower. These wildcats still met the ‘Monitor to breed category’ in which individuals are allowed to breed, and their offspring’s pelage scores are assessed.

As part of the thorough veterinary checks that are done prior to the release of each wildcat, it was found that one of the individuals with a lower pelage score than 16 was cryptorchid. Cryptorchidism refers to the failure of one or both testicles (testes) to descend into the scrotum. As this condition significantly increases the risk of testicular cancer, the decision was made to remove this individual’s testicles to prevent potential complications later in life. As such, this individual cannot breed and will not produce any offspring.

Any potential offspring of the other wildcat with a low scoring pelage will be monitored closely over the coming years to determine the pelage. Given the high genetic scores and pelage scores of the other fertile individuals that were released, we expect that any offspring born of a wildcat pairing will have both high genetic and pelage scores.

The decision was made to release these individuals after careful consideration with the Saving Wildcats Project Management Group (PMG), comprised of representatives from Saving Wildcats project partners, Forestry and Land Scotland, NatureScot and the Cairngorms National Park Authority. All decisions to release wildcats are made on a case-by-case basis by the PMG in relation to their pelage and genetic scores, the composition of the populations at the release site, the relatedness of release cohorts and the progression of the project.

This decision was also made considering several other factors including the fact that:

- Releasing individuals with low scoring pelage could increase the likelihood of other individuals staying in the area, especially their same sex siblings

- There is value from knowledge gain of released animal movements and behaviour, which would inform future wildcat releases.

Our approach to wildcat conservation is to preserve as much valuable wildcat genetic variation as we can from the population in Scotland, so that populations established from released individuals have the biggest chance of being able to adapt to future challenges like diseases and climate change. Without genetic variation, a population cannot evolve in response to changing environmental variables and, as a result, may face an increased risk of extinction.