Catching cats: the art and science of replacing the GPS collar on wild-living wildcats

In the summer of 2023, Saving Wildcats released 19 wildcats into the Cairngorms Connect landscape of the Cairngorms National Park. When the wildcats were fitted with the first GPS-radio collars in May last year, a few weeks prior to release, we expected the collar batteries to last around eight to nine months based on previous research, at which point they would need removing or replacing. We have since decided, with advice from expert advisors, to try and re-collar most of the released wildcats, so we can continue gaining information about their behaviour through their first breeding season.

That means trapping the wildcats and anaesthetising them, which is also a good opportunity for a health check. The planned timeframe for collar removals and replacements was January – February, which works well because it is important to minimise the risk of trapping females when they are likely to be heavily pregnant (we further minimise this risk by monitoring the cats with cameras prior to trapping). It is also easier to trap wildcats over winter, when natural food is less available, and the cats are more likely to come to food baits.

Having said that, trapping wildcats isn’t easy – at any time of year! They are extremely intelligent, with keen senses and they are highly suspicious of traps and food baits. They also occupy large home ranges and move around a lot, particularly the males who are actively searching for females. Fortunately, we have an experienced team: Saving Wildcats project vet Dr Alice Bacon and I worked together trapping and collaring wild-living wildcats for the previous project Scottish Wildcat Action, alongside our colleague at the Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU), Dr Kerry Kilshaw.

It is important to note that all our trapping and collaring work is carried out under licence from NatureScot. Our team has a mobile veterinary unit to attend to the wildcats in the field and lots of technology to allow us to monitor traps 24/7 and respond to a trapped wildcat immediately. We also have the benefit of many months’ worth of tracking data so that we can identify suitable trapping locations with the help of Dr Kerry Kilshaw, who conducts rest site analyses to pinpoint locations where the cats have spent the most time.

One of the first collars to show signs of battery depletion belonged to a female wildcat that we call Aizle, who has been living on Rothiemurchus since she was released in June last year. Although her radio ‘pinger’ was still functioning, the collar stopped recording GPS fixes in mid-January, so the race was on to try and trap her before the ‘pinger’ stopped working too. Fortunately, Aizle has been fairly local to one specific location for several weeks, so we were able to get a trap out quickly.

We start by ‘pre-baiting’ the trap i.e. putting food in every day with the trap locked open and monitoring her visits using trail cameras. We were also able to use a wireless camera in this location, thanks to a strong mobile signal (not always the case, as explained further below), so we get alerts on our phones every time Aizle appears on camera. We were also able to use a trap alarm (in this case, Mink Police), which is fitted to the door of the trap and sends us an immediate alert if the trap has been triggered; we only use this once the trap has actually been set. We had planned to begin trapping from the week beginning 22nd January but unfortunately for us, the weather had other ideas!

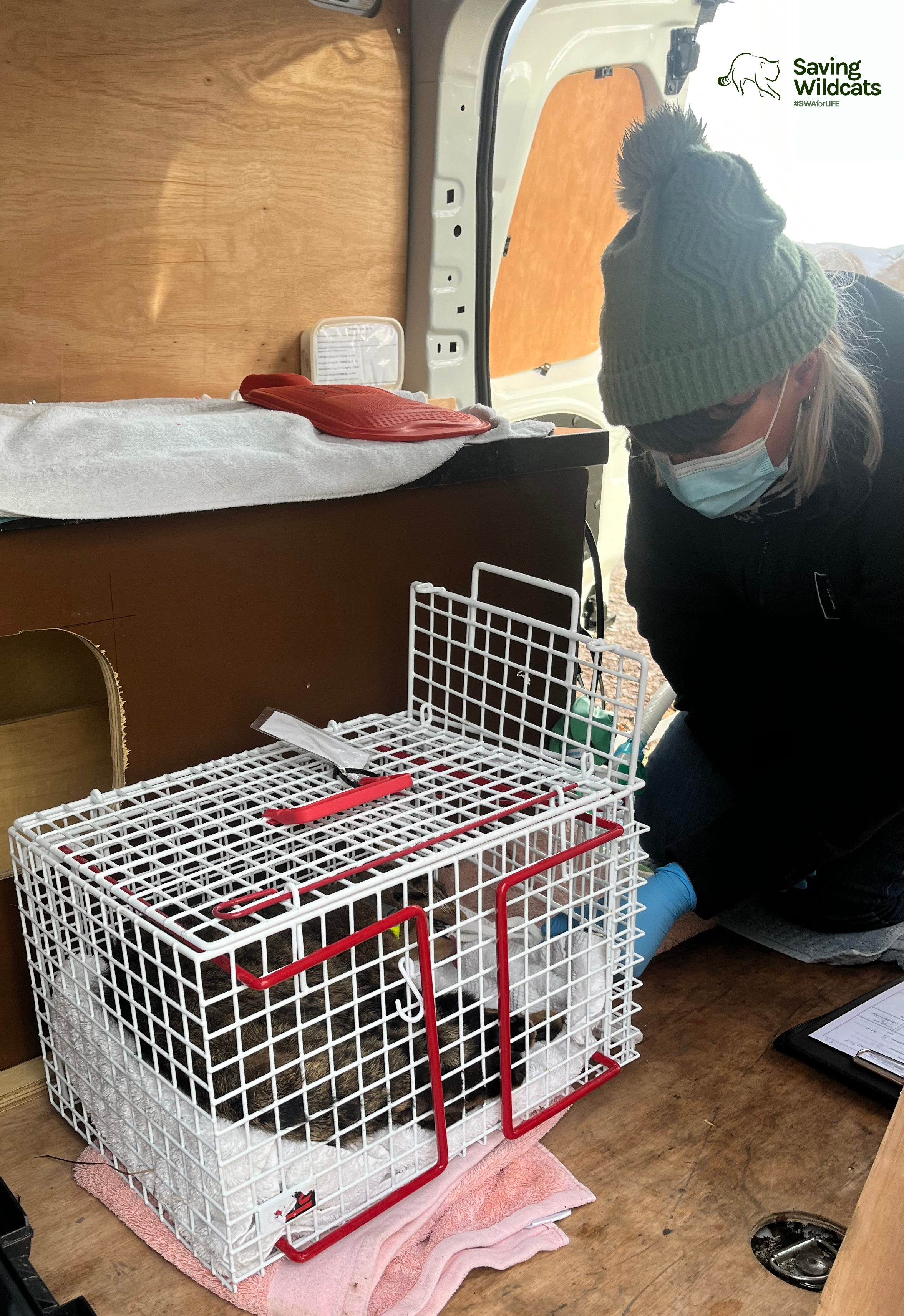

After a week of heavy snow, the weather turned extremely wet and windy and the area around her trap site (along with the rest of Strathspey) was badly flooded. Finally, there was a brief weather window on the morning of 29th January, and we set the trap first thing in the morning. I activated the trap alarm, left the food, and walked back to my van which was parked some distance away. As I settled down to wait, Aizle appeared on the camera, and with my heart in my mouth, I watched her enter the trap and – success! The door closed securely behind her. I returned to the trap immediately to fully cover it with a dark towel (the traps are all covered and waterproof but there are some edges around the door which cannot be totally covered up, as it interferes with the trap mechanism) and then retreated to wait for the vet support, which arrived 20 minutes later. We transferred her quickly from the trap directly to a ‘crush cage’ (a carry cage with an integral ‘squeeze’ panel) which allows the vets to anaesthetise her quickly and without handling. Alice and Dr Rebecca Amos from our Royal Zoological Society of Scotland (RZSS) vet team gave Aizle a thorough health check, while I took photos of her pelage (coat pattern) and prepared the collars for fitting (Images 1 and 2).

If there are any welfare concerns that could be made worse by the addition of a collar, the cat will be released uncollared and treated as appropriate according to veterinary protocols. However, Aizle weighed a very healthy 5kg and was in excellent condition, and there was no sign of the collar having caused any issue, so we made the decision to re-collar and then release her (Image 3). We have to release her in the location that she was trapped, as stipulated by our licence conditions, and so that she knows where she is!

The field team will continue to monitor Aizle with cameras for a week or so after trapping to make sure she settles down ok (she did return to the trap location and take food the same evening, see Image 4). She is in a really nice location on Rothiemurchus, with plenty of food and cover, and we hope that she stays there for a while yet! We are grateful to Rothiemurchus for their help; we wouldn’t be able to do this without the support of local land managers.

We would also like to thank Glenmore Campsite for their help in trapping another of the wildcats, Callie, whose collar was also running out of battery. This time, we had a bigger challenge because there was no mobile signal at the trap location and the wildcat was visiting the trap overnight, which is actually when most of our trapping usually takes place. When the technology works, we can stay locally and attend the trap site immediately at any time of night when the trap alerts go off. Without the technology, we need to go ‘old-school’ and watch that trap in person. All night.

Luckily, I have a small van with a fold out bed inside, and Alice and I are pretty small (!) so with the permission of the campsite, we decided to camp out overnight with the vet van in tow and manually check the trap every two hours, from 5pm onwards. There is a fine line between checking too regularly, and risk scaring the cat off, and not checking often enough, because we don’t want the cat to be in the trap for too long. Callie usually visited the trap between 6-8pm at night (based on our trail camera footage). When there was still no sign of her by 10pm, we thought that would probably be it until the morning, since she also came regularly at 8am. We bedded down for the night and set our alarms for midnight. When the alarm went off, I wandered to the trap in my pyjamas and shone the torch on the door expecting to see it open; but it was shut!

Callie was in the trap and the trail camera showed that she had been in there for 30 minutes, which is a good response time (Image 5). We called our team vet nurse, Louise Stott, who got out of bed and came straight to the site while Alice and I transferred Callie to the ‘crush’ cage. She was quite vocal – growling a bit – but she was quickly transferred and anaesthetised. Callie was found to be in good health and was fitted with a new collar and released a few hours later, once the vet team were happy that she had recovered fully from the anaesthetic. The staff at the campsite were wonderful, allowing us to stay there for free, use their facilities (my tiny van does not have a toilet …) and not batting an eyelid at the thought that we might have to be up and down a bit in the night checking on the trap.

We have been delighted to find the cats healthy and well so far, they have packed on a lot of muscle and weight since their release as they have grown into adulthood. Their body condition tells us they are managing to hunt successfully in the wild… but there is still a long way to go, and trapping is a huge team effort. The field officers work tirelessly in getting traps out and monitoring/pre-baiting multiple sites, while also continuing to track all 18 wildcats, liaise with landowners and managers, and run over 100 camera traps – among many other things! We would like to thank the landowners, land managers, and members of the local community that have been involved in the trapping so far and helped us with the monitoring efforts by reporting their wildcat sightings and allowing us access on their land. We hope that the current success will continue.